|

Background

The decisive defeat of the Russian Baltic Fleet

by the Japanese Combined Fleet at the Battle of Tushima in 1903 helped

usher in several decades’ adherence by the Imperial Japanese Navy to the

idea of a decisive single naval battle deciding the outcome of a war. Subsequent

Japanese naval doctrine was built upon this view, with a titanic battle

between fleets of battleships deciding the outcome of that war. The Washington

Naval Treaty of 1922 served to alter their means of achieving such a victory,

though not the goal itself.

The treaty halted all battleship construction for

ten years, as well as setting ratios of capital ships between the signatories.

As such, Japan found herself at a disadvantage given the 5 (US):5 (UK):3

(Japan) ratio in battleships. To help make up for her quantitative battleline

disadvantage, Japan turned to a relatively unregulated category, that of

cruisers.

Cruisers were not limited by ratios or an overall

tonnage allowance, only that of an individual ship tonnage limit of 10,000tons

and a main battery no bigger than 8 inches/20.3cm. Japan turned her focus

towards building cruisers with maximized armament to supplement the battleline.

Her naval doctrine evolved to include the cruisers as part of an advance

force to help whittle down an enemy fleet prior to engagement by the battleline.

They would do so with high speed, a heavy main battery and torpedoes, and

preferably at night.

Design

At the time of the treaty, the Japanese had already

embarked on an advanced cruiser design utilizing a 20.3cm (8”) battery,

but on a lighter 7,500ton hull which allowed a broadside of only six 20.3cm

mounts. The larger gun, plus surface launched torpedoes, classified the

design as the Type “A” or first class, cruisers for the Japanese. Two such

ships entered service in 1926, known as the Furutaka class. An additional

two ships, the Aoba class, were an improved design on the same size hull.

These entered service in late 1927.

A new class of four vessels was then designed to

take advantage of the new treaty’s 10,000ton hull limit. These were known

as the Myoko class and entered service in 1928-29. Their design was meant

to maximize the armament that could be carried on a 10,000ton hull. The

main battery was increased to ten 20.3cm mounts carried in five twin turrets.

Originally designed without a torpedo armament, subsequent modernizations

eventually included four triple torpedo launchers. Armor protection was

greatly improved, along with the inclusion of an anti-torpedo belt. The

powerplant was also increased in power, as was the ship’s range.

When built, these ships carried the heaviest armament

of any cruiser class yet built. However, the ships were overweight by approximately

10% at 11,633 tons (standard load) and 14,980 tons (full load), mostly

a consequence of attempting to place too much in the way of arms, armor

and equipment on a treaty restricted hull. The extra weight affected their

sea-keeping abilities, along with range. The accommodations for the crew

were also cramped.

A follow-up class was designed to address the shortcomings

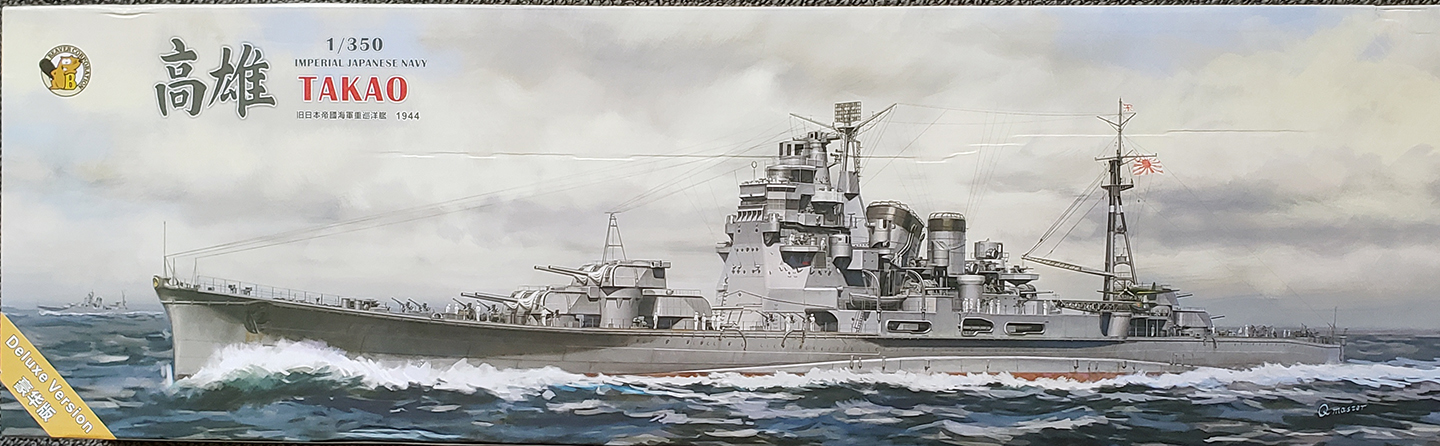

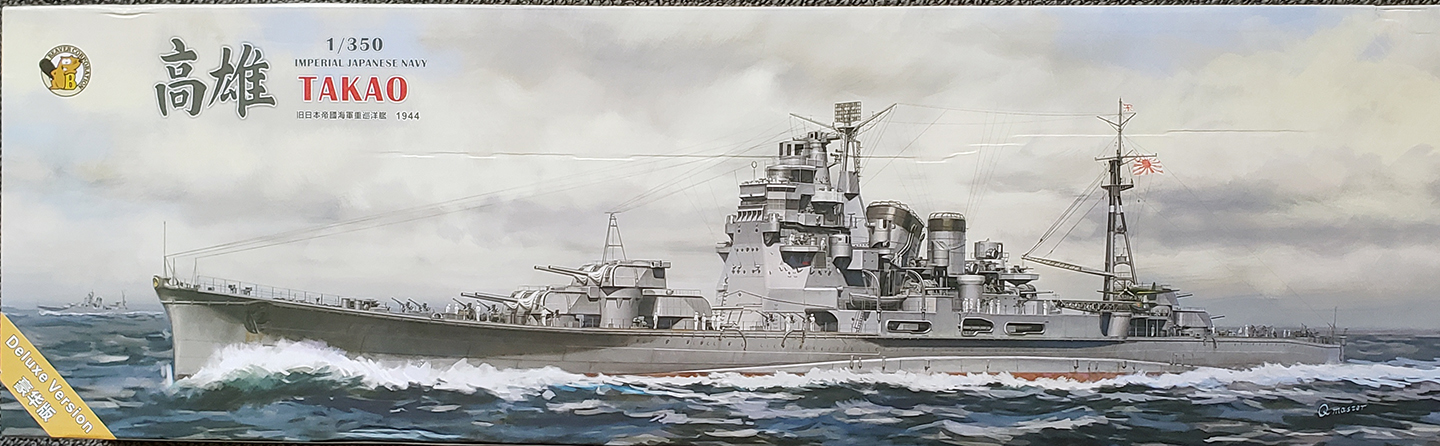

of the Myokos. Known as the Takao class (and consisting of sisters Takao,

Atago, Maya, and Chokai), these ships were approximately the same size

as the Myokos, with a hull 668.5ft. long and 62ft wide as built, and having

a displacement of approximately 12,000tons standard and 15,000 tons at

full load. The Takaos retained the same main gun battery and layout as

the Myokos, but also with improved features and habitability. They entered

service in the early 1930s.

Their bridges were enlarged to accommodate fleet

command and control functionality. The bridge was also moved slightly aft

to reduce the length of the armored citadel. Their hull armor was strengthened

with the use of Ducol steel instead of HT steel and slightly thickened

as well. This was particularly true in the areas surrounding the magazines.

Their rotating twin, four 61cm torpedo batteries were located aft to reduce

potential damage from possible induced explosions. Two catapults for reconnaissance

aircraft were also installed.

Still, this new class was also about 10% overweight,

despite the use of the Ducol steel armor, some electric welding and use

of aluminum in the bridge structures. The large bridge structures added

some degree of instability as well, necessitating the addition of a few

hundred tons of ballast. The Myokos had not yet run their trials when most

of the design work for the Takaos had been completed, so the issues with

weight were not yet completely understood.

All the Takao sisters underwent a refit during

1936 in the wake of the 4th Fleet incident. Their hulls were strengthened

considerably, and minor improvements were made to their masts, fittings,

searchlights and light armaments. In 1937, adjustments were also made to

their fire controls to reduce the dispersions of their main battery salvos.

An extensive modernization was planned for the

class in the 1938-1941 timeframe. Among the planned steps: a reduction

in the size of the bridge to reduce top-weight, the addition of hull bulges

to improve stability, torpedo protection and longitudinal hull strength,

improvements to the powerplant, living quarters, communication facilities/equipment

and flooding/counterflooding abilities, and the modernization of the antiaircraft

armaments, torpedo armaments (increased from two to four per mount), fire

controls, and aircraft handling facilities, as well as the installation

of a new tripod foremast with improved RDF equipment. Upon completion of

the improvements, the Takaos would remain the largest cruisers in the IJN.

Takao was modernized at the Yokosuka Navy Yard

between May,1938 and August,1939. Atago was modernized between April,1938

and October,1939, though her modernization was split between Maizuru Navy

Yard (hull and bridge) and the balance of work performed at Yokosuka. Modernizations

for Chokai and Maya were planned for 1941, after modernizations for the

Myokos and the Mogamis were completed.

However, the run-up to war required all work to

be completed by June 1941. Six months were available for work but considered

impractical given the scope of proposed changes. So, the modernizations

for Maya and Chokai were postponed, and a small refit of their torpedo

and AA armaments took place instead, along with an upgrade to their catapults.

All the sisters received incremental refits throughout

the war, mostly to do with increased AA, improved hull integrity and radar

installations. Maya would notably receive an extensive modernization and

refit as an AA cruiser after incurring extensive bomb damage in 1943.

History

Takao is one of the more famous ships of the Imperial

Japanese Navy, both as name ship of her class, and in her own right. She

was laid down on April 27, 1928, and commissioned on May 31, 1932. All

four sisters were commissioned within a three-month interval and collectively

designated as Cruiser Division (Sentai) 4. All would train together throughout

the 1930s, excepting those times when the sisters underwent refits or modernization.

Additionally, they jointly supported landings near Shanghai during the

start of the Sino-Japanese war in 1937, as well patrol the waters off northeast

China.

At the outset of the Pacific War in late 1941,

Takao and Sentai 4 participated in the landings in the Philippines, then

spent much of February and March 1942 operating in the waters off the Netherlands

East Indies out of Palau and subsequently, Staring Bay. From there, Takao

helped intercept Allied shipping trying to escape as the Japanese overran

those islands. She sank multiple merchant ships as well as several lighter

naval units from the Allied ABDA forces.

She returned to Yokosuka in mid-March 1942 and

received a light refit, including additional 25mm AA guns and the replacement

of her secondary battery of four 12cm mounts with four unshielded, twin

12.7cm mounts. Still at Yokosuka in late April, she sortied in the company

of Maya and Atago as part of an unsuccessful pursuit of USN TF-16 (the

Doolittle Force) that had bombed Japan, using B-25 bombers flown from the

deck of the carrier Hornet. In early May, she and Maya rescued crew from

the sinking seaplane tender Mizuho, torpedoed by USS Drum off the coast

of Japan.

In late May, Takao and Maya joined with the Northern

Force for the successful attack on Dutch Harbor and the capture of Attu

and Kiska Islands in the Aleutian Islands in early June. Both ships returned

to northern Japan, then sortied again as a convoy escort for a resupply

mission to those same islands. They subsequently returned to Japan.

In early July, Chokai was detached from Sentai

4 to act as flagship for the newly formed 8th Fleet, charged with operations

in the South Pacific. After the invasion of the island of Guadalcanal by

American Marines in early August, the other three sisters of Sentai 4 advanced

to the fleet anchorage at Truk Atoll along with other heavy elements of

the fleet. They were staged at Truk as part of a larger plan to retake

Guadalcanal.

In mid-August, the Japanese initiated their plan

by sending a heavily escorted reinforcement convoy to Guadalcanal from

Truk. On the 21st, three Japanese task forces departed as well in support.

One was a carrier group, the other two were surface forces looking to entrap

and destroy elements of the US fleet after the carriers had neutralized

any interference from US carriers and land-based air assets utilizing a

crude airstrip known as Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. Sentai 4 was part

of the Japanese “Advance Force”.

In what is now known as the Battle of the Eastern

Solomons on August 24-25, only the Japanese carrier group and ships of

the Reinforcement convoy engaged American forces. The Japanese lost a light

carrier, a destroyer, and several transports, while suffering considerable

damage to a fleet carrier, a light cruiser and a seaplane tender, along

with the loss of many aircrews. A US fleet carrier was heavily damaged,

but air crew losses were low. Neither Takao nor her sisters saw any action.

All Japanese fleet elements returned to Truk. There

were several operational sorties from Truk throughout September for Sentai

4 and the Japanese fleet, but without any consequential actions or engagements.

That changed in October when Takao and Sentai 4 sortied with the Japanese

fleet as part of a new operation to retake Guadalcanal. The ensuing confrontation

is known as the Battle for the Santa Cruz Islands.

Again, Sentai 4 was part of a large surface task

force. Also again, the battle was primarily a clash between opposing carrier

forces, with significant damage and losses to both sides. Losses were high

on both sides regarding carrier air crews, but more so for the Japanese.

More importantly, the Japanese effort failed short of retaking Henderson

Field on Guadalcanal; the ownership of the airfield now acknowledged as

being the key to success for either side. Sentai 4 again failed to see

any action.

Once more, the Japanese fleet returned to Truk.

Still another attempt to retake the field was planned for November. Various

heavy units of the fleet, including Maya but not Takao or Atago, participated

in several nighttime bombardments of Henderson Field to destroy American

air forces based there. These were only momentarily successful, but they

did help set the stage for several battles over several days that took

place in mid-November. These encounters became known as the Naval Battles

for Guadalcanal.

A first clash between IJN and USN forces occurred

on the night of November 12-13th, in which ships engaged each other at

very close range for almost 40 minutes. The outcome was costly, yet indecisive.

The Japanese lost one battleship and two destroyers in this encounter,

with many other IJN ships suffering various amounts of damage. In turn,

the American lost two light cruisers and four destroyers, plus several

of their remaining ships incurring various amounts of damage.

This first round had not included any members of

Sentai 4, but the following night, Maya returned to bombard Henderson Field

in the company of heavy cruiser Suzuya while sister Chokai, heavy cruiser

Kinugasa, and several destroyers acted as a covering force and distant

escort for a large group of transports headed to Guadalcanal with troop

reinforcements. The night’s bombardment proved ineffective because the

following morning, surviving aircraft from Henderson Field, in conjunction

with aircraft from the carrier Enterprise, inflicted considerable damage

and loss upon this cruiser force as well as the transport force. Kinugasa

was sunk and Maya was moderately damaged by a dive bomber that inadvertently

crashed into her,

Subsequently, Atago and Takao, along with the battleship

Kirishima, two light cruisers and eleven destroyers were tasked with one

more bombardment of Henderson Field on the successive night of November

14-15. In doing so, they clashed yet again at close range with an ad hoc

USN force of two battleships and four destroyers similarly tasked with

preventing the bombardment by the Japanese.

Despite damaging one of the American battleships

and sinking three destroyers, the Japanese were again denied the opportunity

to eliminate or retake Henderson Field. They also lost Kirishima and a

destroyer, while Atago incurred light damage. Atago and Takao did score

several gunfire hits of multiple calipers upon the first US battleship

(South Dakota) but missed in their attempts to torpedo the second USN battleship

(Washington).

Afterwards, Sentai 4 retired toward Truk with the

remaining IJN forces. Takao and Atago eventually returned to Kure, Japan

at the end of November for a short refit.

In January 1943, Takao returned to Truk, eventually

participating as part of the supporting forces accompanying the successful

evacuation of Guadalcanal by Japanese destroyers over several nights in

early February. Afterwards, she remained at Truk with Atago and other heavy

elements of the Fleet until July.

Takao and Atago returned to Yokosuka at the end

of July for further refits and some upgrades. Among them were the addition

of two triple 25mm AA mounts and windshields for the compass bridge level.

More significant was the addition of a Type 21 air search radar atop the

foremast. Within the foremast, the RDF room was converted to a radar monitoring

compartment and the RDF monitoring function moved within the bridge.

Takao returned to Truk in August with other heavy

elements of the fleet. September and October were spent mostly at Truk,

excepting some sorties with the fleet in attempts to intercept various

American task forces as they conducted raids on Wake and various other

movements.

On November 1st, American amphibious forces invaded

the island of Bougainville, which was further up the Solomons Islands chain

to the northwest from Guadalcanal. The Japanese reacted immediately, sending

troop transports and a covering cruiser/destroyer force. The Japanese forces

ran into a similar USN cruiser /destroyer task force, which inflicted losses

and damage to the Japanese with little of their own. This encounter, the

Battle for Empress Augusta Bay, also denied the Japanese the opportunity

to land their reinforcements.

A larger, more powerful Japanese force including

Takao, Atago, and Maya of Sentai 4, plus four other heavy cruisers, three

light cruisers, and eleven destroyers were gathered at Truk for another

attack against the American forces on and around Bougainville. This force

departed Truk on the 3rd and after a quick 800-mile trip, entered Rabaul’s

harbor around 6AM, November 5th. Several of the ships proceeded to refuel

from tankers already stationed at Rabaul.

As a means of forestalling this new force, the

US Navy took a very serious, calculated risk and sent two aircraft carriers

(the fleet carrier Saratoga and the light carrier Princeton) to attack

this cruiser/destroyer force while at Rabaul. Around noon that same day

of November 5th, 97 US-carrier based aircraft from this carrier group attacked

the Japanese cruiser force in Rabaul Harbor. An hour later, a small group

of land-based B-24s of the US Fifth Air Force made a follow-up attack as

part of a coordinated effort to inflict maximum damage upon the Japanese.

Five of the seven heavy cruisers were damaged,

four (Takao, Atago, Maya, and Mogami) badly enough to warrant a return

to Japan. A light cruiser and three destroyers were also damaged. Takao

was hit by two 500lb. bombs near numbers one and two turrets. 23 men in

turret number one were killed, and her hull holed below the waterline.

Accompanied by Atago (three near missed bombs also holed her below the

waterline and killed 22 men), she returned to Yokosuka Naval Yard for repairs,

arriving on November 15th.

During Takao’s time in drydock, her battle damage

was repaired, she had a refit and underwent some modifications. Her watertight

integrity was improved with the sealing of her lower row of portholes.

She saw the addition of eight single 25mm AA mounts and a Type 22 surface

search radar was fitted to the top of her bridge superstructure. It was

also likely at this time that a Type 93 Mod 2 hydrophone was installed

up forward under the waterline. Atago’s refit was identical.

Repairs were completed on January 18, 1944. Takao

sailed for Truk in the company of several ships, but she and destroyer

Tamanami were diverted to assist the escort carrier Unyo. Unyo’s bow had

been lost to a torpedo hit, with damage compounded by rough seas. With

the assistance of other destroyers warding off US subs, Unyo was successfully

escorted back to Yokosuka.

Takao departed again, this time for Palau, arriving

on February 20th. There, she joined with Sentai 4 sisters Atago and Chokai,

along with Sentai 5’s Myoko and Haguro. Collectively, they conducted training

exercises. Sentai 4 was also transferred administratively to Admiral Ozama’s

First Mobile Fleet.

Both Sentai 4 and 5 departed Palau on March 29th,

accompanied by several escorts, to join the main fleet (now called the

First Mobile Fleet) at its new anchorage at Lingga Roads, Singapore. They

stopped enroute at Davao, Philippines. Departing Davao, the cruiser force

was attacked by US submarines, but all torpedoes were avoided. This force

arrived at Lingga on Apil 9th. Between that date and May 11, Takao and

Sentai 4 conducted training and simple maintenance, as did all the other

elements of the fleet. In the meantime, sistership Maya had rejoined Sentai

4 on May 1st, resulting in the Sentai being fully constituted.

The entire fleet moved again to Tawi Tawi, an anchorage

off Borneo’s Tarakan Island which adjoined the Philippines Tawi Tawi Islands

group, arriving on May 13th. It did so to be closer to fuel supplies and

a potential fleet action. The fleet action came about a month later, when

the First Mobile fleet sortied on June 13th to interdict American forces

planning to invade Saipan and the Marianas Islands. The ensuing battle

was called the Battle of the Philippine Sea.

The Japanese fleet sortied in three task forces,

each built around a core of three aircraft carriers. Sentai 4 sortied with

the task force known as the Vanguard Force. This group, with three light

carriers and a heavy escort of four battleships, eight heavy cruisers,

one light cruiser and seven destroyers, was placed 100 miles in front of

the two main carrier task forces as an intercept force.

Fleet combat took place between June 19 – 20th.

The battle was a disaster for the Japanese. Three fleet carriers and three

fleet oil tankers were sunk, along with several submarines. Worse, Japan

lost about 350 carrier-based aircraft and another 100+ land-based aircraft.

Still worse was the loss of the large number of air crews. American losses

were about 110+ aircraft and associated air crew. The battle essentially

eliminated the Japanese carrier force as a viable fighting force. Sentai

4 did not directly engage in any action.

The First Mobile Fleet returned to Japan where

both Takao and Atago underwent another refit at Kure during the last week

of June. This refit lasted until early July. Four more triple 25mm and

twenty-two single 25mm AA mounts were added to Takao’s AA suite. A Type

13 air search radar was fitted to the aft portion of her foremast. Atago’s

refit was again identical to Takao’s.

Takao and Atago departed Kure on July 8th for Singapore,

arriving there on the 16th. For some unclear reason, both ships went back

into drydock at Singapore at the end of the month. Coming out of drydock

after a few days, both ships headed to the Lingga anchorage. Both sisters

circulated between Lingga and Singapore while focused on training until

mid-October.

Aware of American intentions to invade the Philippines,

the Japanese fleet, Sentai 4 included, sortied for Brunei on the 18th,

arriving on the 20th, where all ships refueled. The Japanese again divided

their fleet into three groups. Sentai 4 was included as part of the Center

Force, a very powerful surface group including five battleships, ten heavy

cruisers, two light cruisers and fourteen destroyers. The Center Force’s

orders were to attack and destroy the American landing forces headed for

the island of Leyte.

All the Japanese forces sortied again on the 21st

for battle. The Center Force’s intent, under Admiral Kurita, was to pass

east through the Sibuyan Sea, then traverse the San Bernando Strait, exit

into the Philippine Sea and turn south to hit the landing beaches. But

first, to get to the Sibuyan Sea, the force had to pass through the Palawan

Passage, which is an open, deep-water channel to the west of Palawan Island.

Unfortunately, Sentai 4 faired quite poorly during

this passage. Two US submarines, Darter and Dace, were on patrol in this

area to scout for any Japanese naval force that might be sent to the Philippines

to attack the landings. They sighted the Center Force, radioed several

position reports back to the US fleet, and then raced along the surface

during the night to gain an attack position.

On the morning of October 23rd, the Center Force

was passing through the Palawan Passage when Atago was hit by four torpedoes

from Darter around 5:30AM. She sank shortly thereafter. Maya was hit about

20 minutes later by another four torpedoes from Dace. Maya, too, sank very

quickly. In between these two incidents, Takao was struck by two torpedoes

on the starboard side from Darter. No other Japanese ships were attacked,

and the rest of the Center Force steamed on to confront the US fleet at

the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea the next day and finally at the Battle off

Samar on the 25th, where Japanese losses were heavy, and the mission had

to turn back. The losses included the last of Sentai 4’s sisters, Chokai.

In Takao’s case, the two torpedoes struck aft,

in the vicinity of the aftmost bank of torpedo tubes and again further

aft along the fantail. Boiler rooms three and four were severely damaged,

and Takao lost her outermost starboard propeller shaft. The inboard shaft

was damaged, as was her steering. 33 men were killed and another 30 injured.

Takao came to a halt and was unable to resume headway until 2100 hours,

first making a speed of 6 knots and then gradually increasing to 11 knots.

Steering was problematic using a jury-rigged rudder and destroyers Naganami

and Asashimo had to escort her back to Brunei, arriving back there on October

25th.

After some emergency repairs at Brunei, Takao limped

back to Singapore by November 11th. She entered drydock there in early

January,1945 but the hydraulic steering pump could not be effectively repaired.

Further attempts were made, including additional repairs to the rudder,

in the hope of having Takao be able to return to Japan but these were also

in vain. In March, the decision was made for Takao to remain in Singapore

to help defend the island.

Her damaged stern was removed around frame 337

(between the aftmost propellers and the rudder) and emergency waterproofing

measures applied to the remaining frame. She was then permanently moored

as a floating AA battery. Camouflage paint was applied and non-essential

personnel removed from the ship and placed ashore. Some of her 25mm AA

were also removed and relocated to land-based emplacements.

By summer, her presence in the harbor (along with

the similarly marooned and moored heavy cruiser Myoko) was considered a

potential threat to pending efforts by the British to retake Singapore.

Though her actual material condition was unknown to the Allies, the potential

destructive power of her main batteries could not be ignored. Accordingly,

the Royal Navy dispatched midget submarines with limpet mines and explosive

charges to damage both cruisers.

On July 30-31, the British midget submarine XE3

managed to penetrate Singapore Harbor and attach several limpet mines to

Takao’s hull. The subsequent explosions damaged the hull below the waterline,

flooding several compartments, but without any injuries to Takao’s crew.

A second midget submarine was unable to reach Myoko to attack.

Despite the damage, Takao remained fundamentally

operational, with working boilers and generators. She remained in this

condition until officially surrendered to the British in Singapore on September

21, 1945. Most of her crew were then moved ashore off the ship, but about

150 crew were retained aboard to keep the ship somewhat operational.

Eventually, Takao was taken over by the Royal Navy

and a decision made to scuttle her. On October 27, 1946, Takao was towed

into the Straits of Malacca and explosives placed on her hull bottom. In

the late afternoon of the 29th, her Kingston valves were opened. Around

6:30PM, the explosives were set off. As she settled, the light cruiser

HMS Newfoundland opened fire to help speed her demise. Takao sank stern

first shortly thereafter, joining Myoko on the bottom, as Myoko had been

scuttled in early July. Takao was struck from the Navy Register shortly

thereafter. |